THE VILLAGERS OF COLLINGHAM AND LINTON WHO SERVED IN WORLD WAR ONE

COLLINGHAMANDDISTRICTWARARCHIVE.INFO

CONTACT

CONTACT

Rank Private

Service Number 64830

Service Army

Battalion 9th Battalion

Regiment King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

Killed in Action: 24th August 1918

Commemorated at: Vis-en-Artois Memorial to the Missing, France

| Rank | Number | Unit |

| Private | 39507 | West Yorkshire Regiment |

Trade or Occupation pre-war: Farm labourer

Marital status: Single

* Taken from attestation papers or 1911 census

** Marital status on enlistment or at start of war

- Born in Collingham, Linton or Micklethwaite

- Lived in Collingham, Linton or Micklethwaite immediately prewar or during the war

- Named on war village memorials or Roll of Honour

- Named as an Absent Voter due to Naval or Military Service on the 1918 or 1919 Absent Voter list for Collingham, Linton or Micklethwaite

Biography

Family background

Arthur Bootland was born on the 14th November 1893 in Collingham, the youngest son of 9 children of William Bootland, a farm labourer, and Elizabeth (nee Pickard). Near the start of their married lives, William and Elizabeth lived in Clifford, as their eldest two children, Ada (b~1871) and Anne (b~1873) were born in Clifford while their remaining 7 children were born in Collingham. One of these children, Harry (b. 1888) died at a very young age and Arthur would never have known him. As one of the youngest children of such an extended family, we can imagine an early life at home with the younger members of the family with occasional visits from and to the elder children as they grew up, married and moved away from the family home.

At the time of Arthur’s birth, a number of his elder siblings had already left home - his eldest sister, Ada (b.~1871) was a domestic servant to farmer Edward Burrell in Kirk Deighton and an older brother Walter (b. 1875) was working as a farm servant for Richard Allan in Compton. Arthur’s early life must have been dominated by family events as his elder brothers and sisters married. Ada married Arthur Perkin in 1893, and by 1901 had moved to Elland, Leeds to start her own family; Annie (b.~1873) married Frederick Sweeting at Wetherby Registry Office in 1899, Walter married Christiana Westoby in 1900 and Emma (b.~1881) married Jesse Dean in 1904. Other family events in the early 20th century would have been less happy – on the 13th December 1909, Arthur’s mother Elizabeth died, aged 61, in Compton from breathing difficulties and heart failure brought on by influenza and she was buried in Collingham churchyard. Then, within six months, on 26th May 1910, when Arthur was 17, his elder brother, Fred, died of congestion of the lungs. By 1911 Arthur was a farm labourer in Compton, Collingham.

Service record

Arthur’s service record has not survived and we have to piece his service together from other records. From Arthur’s medal entitlement, we know that he first served as 39507 Private Bootland in the 11th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment (11/W.Yorks) before transfers to the 2/W.Yorks, the 2/5th W.Yorks, the 8/W.Yorks and finally to the 9th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (9/KOYLI) where he got a new service number as 64830 Private Bootland. It is likely, from his initial service number, that he first went overseas around January to February 1917. The complicated series of transfers makes it difficult to pin down exactly where Arthur served, but again evidence from his service number in the Yorkshire Light Infantry suggests that he transferred into that unit around May to July 1918. The other transfers are likely to mark either absence and return from duty due to illness or injury, or simply to make up for losses in other units. Indeed, in April 1918, the history of the KOYLI records that the 9th Battalion lost heavily, with 2 officers killed and 1 missing and 57 other ranks killed and 107 missing. After that the 9th KOYLI Battalion was sent to a quiet sector of the line, marching on 4th May 1918 to St. Omer where they entrained and went via Paris to Bouleuze in Champagne country between Fismes and Rheims. Here they took over quiet trenches. A few new drafts made up their numbers on 20th June 1918. The division moved again on 4th July to Puchevillers and the regimental history records that by 25th July, the battalion was ready for action again. It seems probable that Arthur Bootland was one of the draft of men who transferred into the 9th Battalion KOYLI during these periods on a quiet part of the front.

Arthur Bootland was Killed in Action on 24th August 1918 during part of a series of the Allied attacks now known as the Battle of Albert to clear the Germans from that town and to drive them back. Pte Arthur Bootland was 24 when he died and he has no known grave, being commemorated on the Vis-en-Artois Memorial to the over 9,000 men who fell in the period from 8th August 1918 to the date of the Armistice in the Advance to Victory in Picardy and Artois, between the Somme and Loos and who have no known grave.

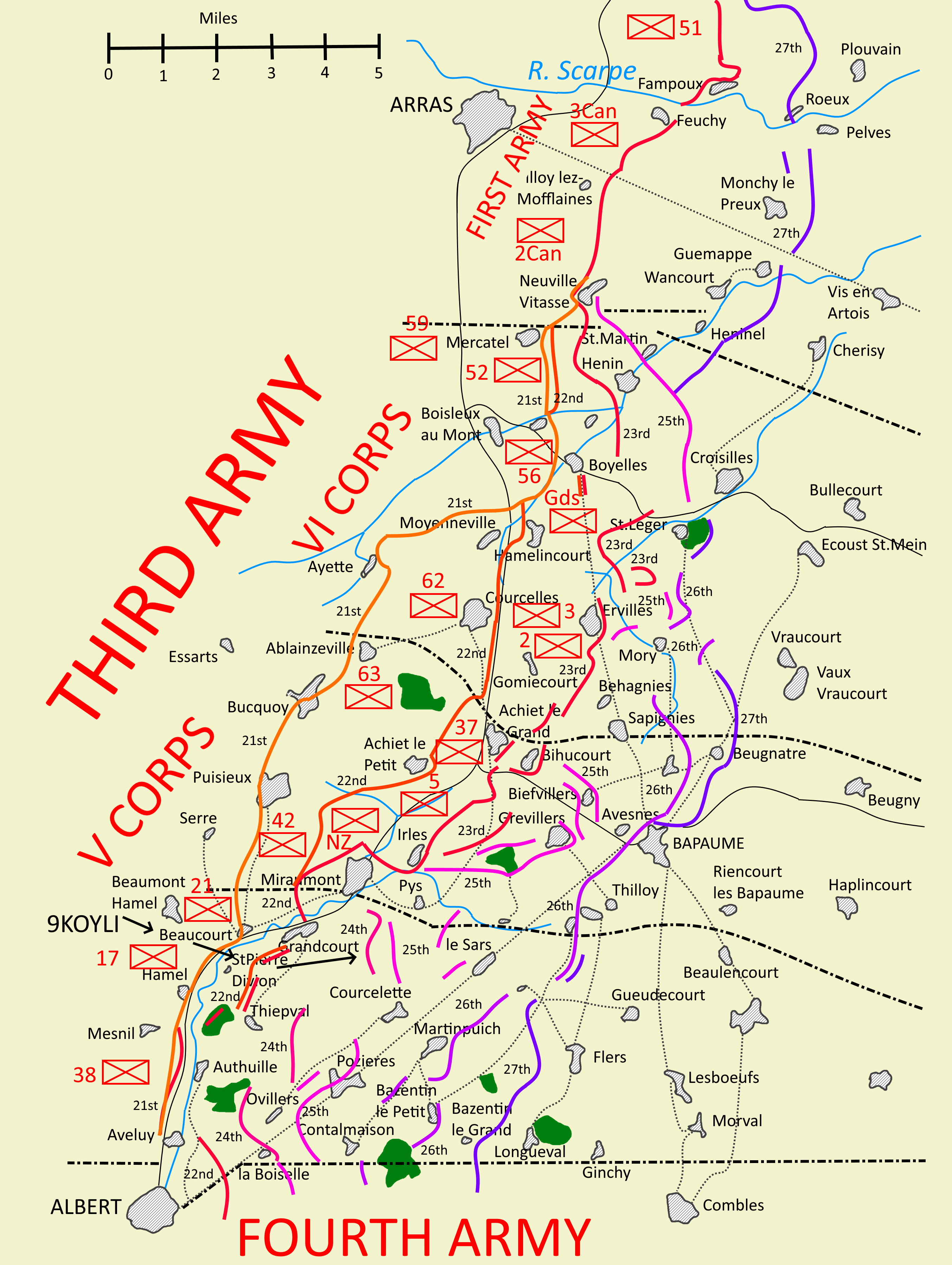

At the time of Arthur's death, the 9th Battalion KOYLI was serving as part of 64th Brigade, 21st Division within V Corps and it is to their records that we must look to find where Arthur was serving when he was killed.

After a number of years of relatively static warfare on the Western Front from 1915 to 1917, the Germans had taken the opportunity of the Russian revolution to switch troops from the Eastern Front and they were able to make significant advances early in 1918. However, after these advances were checked before Amiens, a succession of British advances was made to recapture ground. By August 1918, the Germans had been pushed back, and around Albert were occupying only slightly more ground than they had been during the Somme battles two years previously. The morale of the two sides was now very different. The British and her Allies had stopped a major German advance and the unlimited manpower of the Americans had joined the battles. On the other hand, the Germans had suffered a major defeat and manpower was becoming a limiting factor. In mid to late August 1918, the Allies launched a series of attacks now known as the Battle of Albert to clear the Germans from that town and to drive them back.

Around the 20th August 1918, Arthur's battalion was in training in brigade reserve and then started moving forward to join the next attack. Every day they were under heavy shelling as they moved forward. At the start of these battles, around 22nd-23rd August 1918, V Corps had to cross the River Ancre; not an easy task, as the shell damage to the banks meant that most of the valley was flooded and the main stream was indistinguishable. In fact, the Ancre had become a stretch of marsh and water, covered by a tangle of fallen trees, branches and reeds, with barbed wire added, to make it a more difficult obstacle. The initial aims of V Corps were to extend the British line across the river and to exploit any enemy weaknesses. These aims were carried out mainly by 21st Division led by the 62nd Brigade. They successfully crossed the river and took Beaucourt for the loss of only 30 casualties. Further south however, where Arthur Bootland was serving with the 9/K.O.Y.L.I., the advance was held up by machine gun fire and only at 3.30pm did the 12th and 13th Northumberland Fusiliers (from 62nd Brigade) cross the river. At 8.30pm on the 21st August, 64th Brigade (including Arthur and the 9th Battalion KOYLI) was ordered to cross the river, but it was not able to get a company across until 2am on the 22nd, and it was subsequently attacked and driven back. Despite this setback, the Third Army as a whole had made considerable advances on the 21st August and it was decided to continue the advance, although the main thrust on the 22nd August was to be to the South where the Fourth Army was tasked with the capture of Albert.

Map 1: Third Army Operations August 1918 (click for full size). The advance of third army between 20th and 27th August 1918 is shown. Allied divisions (crossed squares) are shown. Arthur Bootland served with 9th Battalion KOYLI in 64th Brigade, part of 21st Division. Their rough position and movement from 22nd to 24th August is shown. (Figure drawn based on maps in the Official History).

On the 22nd August, according to the their war diary, the 9th KOYLI was in Luminous Trench and, in accordance with G.H.Q. programme, the Third Army (including 9/K.O.Y.L.I) stood fast while troops were prepared for another advance next day. There were some German attacks in the area, but 62nd Brigade formed a defensive flank and repulsed these attacks.

The 23rd August 1918 was a day of great heat, and was disastrous for the German Army. The Third and Fourth British Armies continued their attacks, with the British Third Army being extremely successful in advancing two to four thousand yards on an eleven mile front and capturing a number of villages. The major British attacks and thrust was made in the centre of the British sector and no change of importance took place on 23rd August in the situation of 21st Division on the left wing of V Corps. Another attack was planned for the 24th August, but actually started before midnight on the 23rd. The 9th KOYLI formed up at dusk around 10.30pm and at 11.15pm moved off eastwards. Their planned route was to go via Station Road to Beaucourt and then to Logger Lane, south of the River Ancre.

As we now know, the German troops, beaten in an open encounter by inferior numbers, were obviously discouraged and were inclined to run or to surrender. The British wanted to ensure that this attitude to battle continued. On the 24th August, the day on which Arthur Bootland died, the weather, which had been intensely hot on 21st to 23rd turned cooler and became cloudy and there was some rain and drizzle. V Corps’ orders for the day were to push eastwards towards Rocquigny and Morval, about 8 miles south of Bapaume, as soon as possible, clearing up any pockets of Germans that they encountered. First orders split this attack to the north and south of the obstacles posed by the flooded river to rejoin on the La Boiselle-Ovillers-Grandcourt line. These attacks, to be made at 1am also had the advantage of avoiding a direct attack on the heavily fortified Thiepval position. At the last moment, an alteration to these plans was made due to reports of the demoralisation of the enemy. 21st Division was now directed not to wait for zero hour at 1am, but to press ahead as soon as possible to secure the high ground to the south east of Miraumont, which was still holding out, to cut off the village and to prevent the enemy withdrawing and destroying bridges over the Ancre.

The job of a night advance to attack a defended line and seize an objective over three thousand yards beyond it was an exceptional task and was given to Br. General A. McCulloch of 64th Brigade at 5.30pm on the 23rd August. Before leaving for divisional headquarters at Mailly Maillet, where he was summoned to receive orders, he modified his previous orders so that the brigade (less the 15/Durham L.I. who could not be relieved until after dark) was to concentrate in the ruins of St.Pierre Divion as soon as possible with as many machine guns as could be collected; the section of the Royal Engineers attached to the brigade was to continue working at crossings over the Ancre and mark off crossing places; pack animals and cooks were to be collected at Beaucourt and the brigade Trench Mortar company was to be ready to bombard German positions. Br-General McCulloch learnt at 21st Divisional HQ that no troops would advance to protect his flanks, but that 110th Brigade would follow on the right and 42nd Division on the left and that there would be a short creeping artillery barrage to help him. On return to the brigade in rain and darkness, Br-Gen McCulloch found one company missing, orders to another had not been carried out and that there was little likelihood of the machine guns being ready in time. These problems were to be expected of a hastily planned operation, but did not bode well for the future of a very tough assignment.

The lead in the attack was given to the 9th Bn King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (Arthur Bootland’s battalion) and the 1st Bn East Yorkshire Regiment each less one company – these companies with the available troops from the 15th Bn Durham Light Infantry with eight machine guns to form the reserve. Behind a brigade guide, each battalion had two companies in the front line with the third in support and each company moved in square formation. The general instructions were that any Germans who offered resistance were to be charged at once, and that no notice was to be taken of any who fired from the flank or from a distance, but that each battalion should have a party on its flank to rush out and capture any Germans or machine guns that menaced its flank.

The brigade passed through the trench line of the 62nd Brigade in the dark and shortly after midnight, passing over very rough ground, entered Battery Valley. There it was hit by three bursts of its own artillery fire which should have lifted at 11.45pm and they suffered thirty casualties. Immediately after this the British encountered the first resistance, at 15 yards range, from enemy outposts. These were rushed without hesitation, several Germans being killed and thirty taken prisoner. After this, the brigade advanced confidently, continually rushing German parties and taking prisoners until, about 1am, the intermediate objective was reached and some re-organisation was made to make up for men lost. At this point, some Germans to the south opened fire and because of the isolated position of the brigade (in the absence of the 15/Durham L.I.) and the number of Germans around, Br-Gen McCulloch postponed further advance until 3.15am when he hoped 110th Brigade would have arrived. At 2.15am the 15/Durham L.I. arrived and at 3.15am the advance was continued with the 15/Durham L.I. on the right. Some opposition was encountered from a ravine on the left (probably Boom Ravine which 9 KOYLI occupied), but after some Germans were killed or taken prisoner, the rest fled in all directions discarding rifles and equipment. The K.O.Y.L.I. reached the final objective at 4.30am. 45 minutes later the 15 Durham L.I. formed a short defensive right flank and the East Yorks., who were unable to quite reach the K.O.Y.L.I. lines formed a flank on the left.

Day had by now broken, and Br-Gen McCulloch was badly wounded and command passed to Lt.Col. C.E.R. Holroyd-Smyth of the Durham Light Infantry. No reinforcements had arrived and the brigade was in a precarious position with both flanks in the air and suffering many casualties from constant harassing rifle and machine gun fire from all sides. Counter attacks were made on the battalion and calls to surrender made by the Germans. No notice was taken and every enemy attack was repulsed. Around midday on the 24th August, and because of the general advance of the British on that day, the Germans retired and left the brigade in relative peace. Thus ended the day for the 21st Division – a highly successful day with La Boiselle, Ovillers, Pozières, Thiepval and Grandcourt all captured and considerable ground taken. There was still a wide gap between the 17th and 21st Divisions around Courcelette, but the enemy was in no position to exploit this.

Major-General Sir Andrew Jameson McCulloch KBE, CB, DSO, DCM, DL (14 July 1876 – 19 April 1960) survived the war. He had enlisted as a private soldier in the City of London Imperial Volunteers and then transferred to the Highland Light Infantry in August 1900 and saw action in the Second Boer War. He then commanded the 9th Battalion, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry from October 1917 and then the 64th Infantry Brigade from July 1917 during the First World War. After the war he became commander of 62nd Infantry Brigade in 1919, commander of 2nd Infantry Brigade at Aldershot in 1926 and Commandant of the Senior Officers' School at Sheerness in 1930. He went on to be General Officer Commanding 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division in 1934, temporary commander of the Troops in Malta in 1935 and then General Officer Commanding 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division again from 1936 until he retired in 1938.

At some stage of the fighting on 24th August Pte Arthur Bootland was killed – perhaps as a casualty of friendly fire, perhaps in the initial skirmishes with the Germans or maybe in the final enemy attempts to dislodge the attackers – we will probably never known. Pte Bootland was 24 when he died and he has no known grave, being commemorated on the Vis-en-Artois Memorial to the over 9,000 men who fell in the period from 8th August 1918 to the date of the Armistice in the Advance to Victory in Picardy and Artois, between the Somme and Loos and who have no known grave.

Arthur's eldest brother, Walter Bootland, also lost his life during World War One.

Biography last updated 16 April 2021 13:01:44.

Sources

1911 Census. The National Archives. Class RG14 Piece 25962

First World War Medal Index Cards. The National Archives (WO372).

First World War Medal Index Rolls. The National Archives (WO329).

War Diary of 9th Battalion KOYLI (WO95/2162) The National Archives.

War Diary of 64 Bde HQ (WO95/2160) The National Archives.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery and Burial Reports

Pension Record Cards and Ledgers. Case number 11/D/115490

If you have any photographs or further details about this person we would be pleased to hear from you. Please contact us via: alan.berry@collinghamanddistrictwararchive.info