THE VILLAGERS OF COLLINGHAM AND LINTON WHO SERVED IN WORLD WAR ONE

COLLINGHAMANDDISTRICTWARARCHIVE.INFO

CONTACT

CONTACT

Army structure and Orders of Battle (ORBATS)

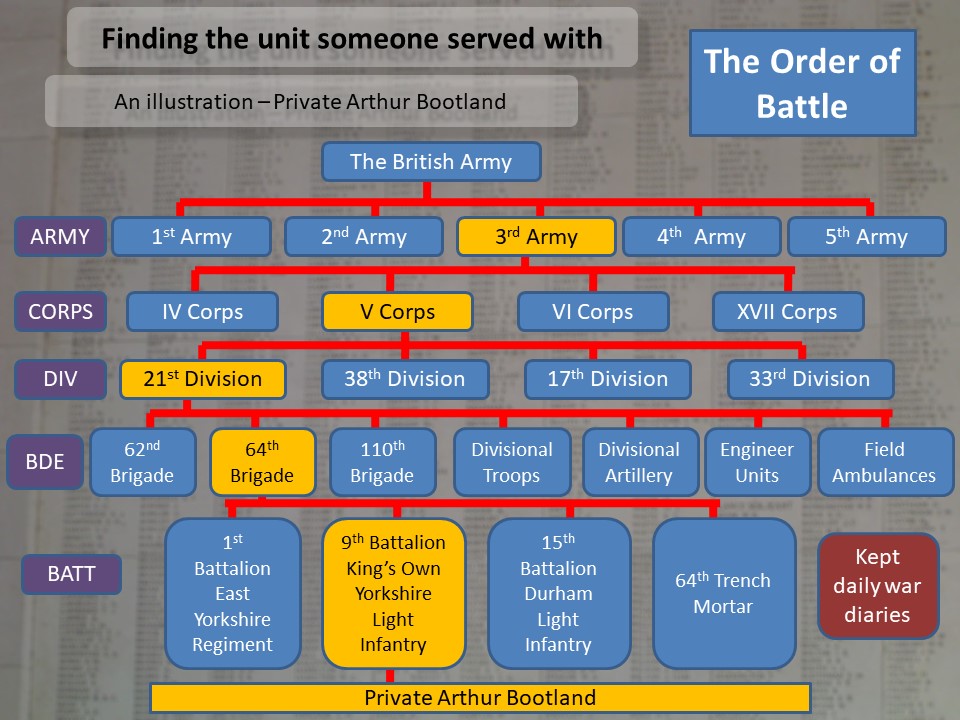

In order to understand fully the descriptions of the military service of each man, we need to understand a little of the Army Structure during the Great War and of the records of the units. Starting with the largest unit, the British Army was divided into units confusingly known as Armies – for example the 4th Army. During the 1914-1918 war, there were five British Armies, each of about 250,000 to 350,000 men.

The next sub-division of an Army was a Corps. These are numbered in Roman Numerals. In the Great War, an Army typically had three to six Corps. First World War Corps were numbered from I to XXII and were allocated to the five Armies, but this allocation changed frequently between 1914 and 1918.

Next, each Corps was divided into about four Divisions. A Division is the smallest, completely self-contained, fighting unit in the army with a total strength in the First World War in fighting and supplementary troops (transport, artillery etc) of about 18,000 men, 4,000 horses and 850 wagons. There were over 70 such Divisions, numbered 1st, 2nd etc up to 71st, plus three Cavalry Divisions.

The next sub-division was a Brigade. Each numbered Brigade was allocated to a Division normally at a rate of three Brigades per Division.

Each Brigade was sub-divided again into four Battalions. A Battalion was therefore about a quarter of a Brigade, but it was also a sub-division of a Regiment. Regiments were named bodies of men, in the Great War usually associated with a town or county. During peace time about 2,000 men in a Regiment were divided into two Battalions of 1,000. During the War, towns often raised many Battalions, and each were given a Regimental Battalion name, eg 9th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment (and these names are usually abbreviated e.g. 9/West Yorks).

Battalions were further sub-divided into Companies, Platoons (about 30-50 men) and Sections (10-15 men). It is very rare that it is possible to identify which company, platoon or section a man belonged to.

Further complications arise from the use of the term Brigade in the Artillery. These Brigades have a different meaning to those in the infantry. Each Division had four Brigades of Artillery attached to it, each having four Batteries of four guns – giving a Division a normal strength of 64 guns. Artillery Brigades were numbered in Roman Numerals and high numbers (eg CCXXII (222)) are common. Batteries within a Brigade were numbered A, B, C and D or depending on the type of Artillery. During the War the allocation of Batteries and Brigades of Artillery changed many times. This makes tracing the army service of artillerymen particularly difficult.

To draw an example of the various units that a man was associated with: Private Arthur Bootland (described elsewhere on this web site (see here)) was, at the time of his death, a member of the 9th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (9/KOYLI). The distribution of Battalions into Divisions, Corps and Armies are described in the "Order of Battle" (ORBAT). Part of the Order of Battle for 9/KOYLI in August 1918 (see below) shows that it was part of 64th Brigade, itself part of 21st Division within V Corps in the Third Army. To get a full picture of Private Bootland’s experiences, we will need to see not only what the 9th Battalion KOYLI were doing, but also how its actions interlinked with those of the other units of 64th Brigade, 21st Division and V Corps. Similar Orders of Battle are described for each man as appropriate on their individual pages.

During 1914 to 1918, each unit of Battalion size or larger kept a War Diary. Many of these diaries survive and are held in The National Archives in Kew. Those for the larger units usually concern the general strategy of the war, and don’t provide much information on the soldier’s life. The most important sources are therefore the Battalion War Diary and the Brigade War Diary. The diary was kept each day by a responsible officer, usually the Adjutant, from information passed to him. Entries can vary from single words (eg "Training") to several pages per day when a Battalion was involved in a major battle. Names of private soldiers are rarely mentioned and so we can only gain a picture of life for the men, without knowing exactly where a man was and what he was doing. This problem becomes acute when single companies are split away from the main unit for a specific purpose, as it is difficult or impossible to find which company a man was serving in and we will be unable to tell which group of men to follow for a particular man’s experience. Another problem is encountered in trying to track the exact date a man joined his unit, especially if he joined in France as part of a reinforcement, since most War Diaries report only bare details such as "20 ORs (other ranks) joined". To these problems we must also add that Battalions and Brigades did sometimes change the higher unit they were affiliated to, and individual men did not always stay with the same unit throughout the war. On many of the individual pages a table is provided showing the various units that each man served in. Despite these problems, War Diaries form a major source when trying to track the wartime experiences of the men, and much use has been made of them.

There are specific problems associated with tracking the military careers and locations of men who served in certain units. For the men named on this web site we have found particular difficulties with men of The Royal Army Service Corps, The Royal Army Medical Corps, The Royal Engineers, The Machine Gun Corps and The Tank Corps.

The Machine Gun Corps

The Army started the war with only limited numbers of machine guns per division and after a year of the war it became apparent that more were needed and that trained men should man these guns, who were not only thoroughly conversant with their weapons but who also understood how they should be best deployed for maximum effect. In 1915 the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) was formed to provide heavy machine-gun teams from machine gunners from battalions. The Machine Gun Corps was formed in October 1915 with Infantry, Cavalry, and Motor branches, followed in 1916 by the Heavy Branch. A depot and training centre was established at Belton Park in Grantham, Lincolnshire, and a base depôt at Camiers in France.

- The Infantry Branch was by far the largest section and was formed by the transfer of battalion machine gun sections to the MGC. These sections were grouped into Brigade Machine Gun Companies, three per division. New companies were raised at Grantham. In total there were around 290 Machine Gun Companies. Unfortunately the record of which company a man served with are not recorded. In 1917, a fourth company was added to each division. In February and March 1918, the four companies in each division were formed into a Machine Gun Battalion. The medal records for World War 1 do not usually identify which company or even which Battalion a man served with, and only later in the war do we sometimes find the MGC Battalion number that a man served with. This makes it difficult to track a man's military service.

- The Guards Division formed its own machine gun support unit, the Guards Machine Gun Regiment. We have not found any Collingham, Linton or Micklethwaite man who served in this unit.

- The Cavalry Branch consisted of Machine Gun Squadrons, one per cavalry brigade. Again medal records do not usually identify these squadrons. No man from our villages have been identified in these units.

- The Motor Branch was formed by absorbing the Motorised Machine Gun Sections (MMGS) and the armoured car squadrons of the recently disbanded Royal Naval Armoured Car Service. It formed several types of units: motor cycle batteries, light armoured motor batteries (LAMB) and light car patrols. As well as motor cycles, other vehicles used included Rolls-Royce and Ford Model T cars.

- The Heavy Section was formed in March 1916, becoming the Heavy Branch in November of that year. Men of this branch crewed the first tanks in action at Flers, during the Battle of the Somme in September 1916. In July 1917, the Heavy Branch separated from the MGC to become the Tank Corps, later called the Royal Tank Regiment. Once again it is hard to place an individual man in any of these individual sections, making it hard to track an individual's service.

Tank Corps

The Tank Corps was formed as the Heavy Section Machine Gun Corps in 1916. Tanks were used for the first time in action in the battle of the Somme on 15 September 1916. The intention being that they would crush the barbed wire for the infantry, then cross the trenches and exploit any breakthrough behind the German lines. In November 1916, they were renamed the Heavy Branch MGC and in June 1917, the Tank Corps. Tanks were initially organised in Companies of the Heavy Branch MGC, and were designated designated A, B, C and D; each company of four sections had six tanks, three male and three female versions (artillery or machine guns), with one tank held as a company reserve. In November 1916, each company was reformed as a battalion of three companies, with plans to increase the Corps to 20 battalions, each Tank Battalion had a complement of 32 officers and 374 men. Some 22,000 men had served in the Tank Corps by the end of the war, but the reorganisations and the lack of specific detail on medal rolls means that identifying specific locations and actions that an individual took part in can be very difficult.

The Army Service Corps (ASC), later the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC)

The Army Service Corps (ASC) operated the transport system to deliver men, ammunition and all manner of supplies to the front. The Army Service Corps gained the prefix Royal- in 1918. The ASC/RASC increased from 12,000 men at the start of the war, to over 300,000 by November 1918. They provided horsed and mechanical transport companies, the Army Remount Service and ASC Labour companies. Men of the ASC/RASC served in their own Corps, but were often embedded with other units (for example with artillery). This, coupled with the fact that specific ASC companies are not often identified on medal rolls etc, means it can be difficult to trace relevant war diaries to associate with a specific man.

Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) supplied the doctors, casualty evacuation, field ambulances and hospitals for the army. The doctors were officers and can be traced through the surviving World War 1 officer's records at The National Archives. However other ranks, who served as stretcher bearers, orderlies, etc are much harder to trace. Effectively it comes to the fact that surviving records do often not detail the specific unit (field ambulance, casualty clearing station or hospital) in which the man served.

The Royal Engineers

No unit was so diverse and vital to the war effort as The Royal Engineers. During the war The Royal Engineers reached an establishment number of 15,000 officers and 300,000 men. Royal Engineers were involved in transportation, supply, ordnance, and labour as well as in specialist units concerned with tunnelling, the use of gas, postal sections, railways, tramways, searchlights, bakeries, bridges, water supply and many many other aspects. Unless specific units are detailed in a man's service record it is almost impossible to identify which of these area a man supported, or where he served, and this specific information is usually not recorded on surviving records such as the medal index cards or medal rolls.